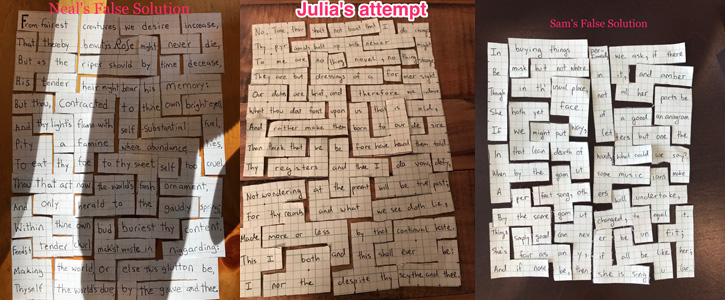

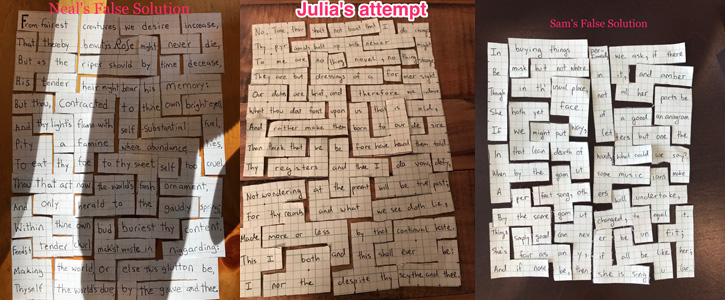

When we began sharing our sonnet puzzles with friends and colleagues, we realized that a puzzle solver might assemble loose pieces in a promisingly rectangular shape, but not the one in which the words were ordered as authored. In many cases the solver composed new lines of verse that read as plausibly Shakespearean but didn’t belong to the original. We developed some vocabulary to clarify this puzzling situation — a jargon. When a solver assembles one of our poem-puzzles into a rectangular sonnet shape but doesn’t get the pieces in the right place, that is, doesn’t put the words where the author put them, we say that he or she has found a false solution.

In an essay coauthored by puzzle maker Stewart Coffin and the puzzle collector Jerry Slocum, a puzzle named “Nice Try” (AP-ART no. 179) is shown supporting, likewise, what Slocum and Coffin call an “incongruous solution.” For Coffin, the failure to isolate a single, elegant solution (packing the frame with the shapes and leaving a void in the center) meant the puzzle is to be sent to “the ever-growing trash bin labeled ‘nice try.’“1

Because our group is as interested in the generation of new poems as we are in the analysis of existing ones, we welcome incongruity (unlike Slocum, who aims as a designer to create problems with solutions) and endorse the oxymoronic tension between “false” or “incongruous” and “solution.” Solomon W. Golomb’s seminal study of Polyominoes makes a distinction between data and pattern that we find illuminating in this context: “There is a lesson in plausible reasoning to be learned from the pentominoes. Given certain basic data, one labors long and hard to fit them into a pattern. Having succeeded, one then believes the pattern to be the only one that ‘fits the facts,’ indeed, that the data are merely manifestations of the beautiful, comprehensive whole constructed from them.”2

For a student solving a poem-puzzle this fitting of facts means that two or more likely pieces may seem to lock in a solution. And we have watched many friends and students convince themselves that they have uncovered a syntactical pattern when they have, in fact, imposed it upon the pieces. Two or three pieces fit together in a series of credibly Shakespearean phrases can stall and frustrate a solver who aims at recreating the pre-existing sonnet.

However, if it’s not solutions that are desired but new arrangements of the constituent pieces, then the “pentominoes illustrate that many different patterns may be constructed from the same data, all equally valid, and that the nature of the final pattern is determined more by the desired shape than by the information at hand” (Ibid.) Of course, Golomb, a mathematician, is thinking of pure shapes free of syntactical and grammatical constraints, but his fundamental principle holds that many different patterns can be constructed from the same given set of pieces. Coffin warns alternately that a “designer must always test thoroughly for unintended false solutions” (5).

And yet, once a poem puzzler is told that she has arrived at a false or incongruous solution, she may accept the idea that prosody and a set vocabulary support multiple arrangements. In the matrix of false and multiple solutions, we apprehend generative potential: new poems cast from controlled vocabularies. It is for this reason that our Increase project focuses on the first seventeen of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, the so-called “procreation” sonnets, which thematize creativity and multiplication. From out of the set of sonnets piecified, we will educe by ingenuity or brute force (or perhaps both) a new 18th sonnet.